The more we demand, the more we get de-activated (from the platform)… and the more important it is to build bargaining power for platform workers through a “task force for Gig Workers”

“In the next ten years, the economy driven by digital technology will gradually transform employment as we know it. In Europe and industrialized countries, labor laws are adjusted to changing employment conditions.”

It is a great thing that the Department of Labor Protection and Welfare, Ministry of Digital Economics for Economy and Society, and various NGOs came together to listen and find ways to improve the labor situation in the country, the same which happened in Germany. “We must always be discussing this issue because employment conditions are ever-changing. It may be time to form a task force to protect workers’ rights in these changing conditions,” says Resna Rodic, Director of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, Thailand.

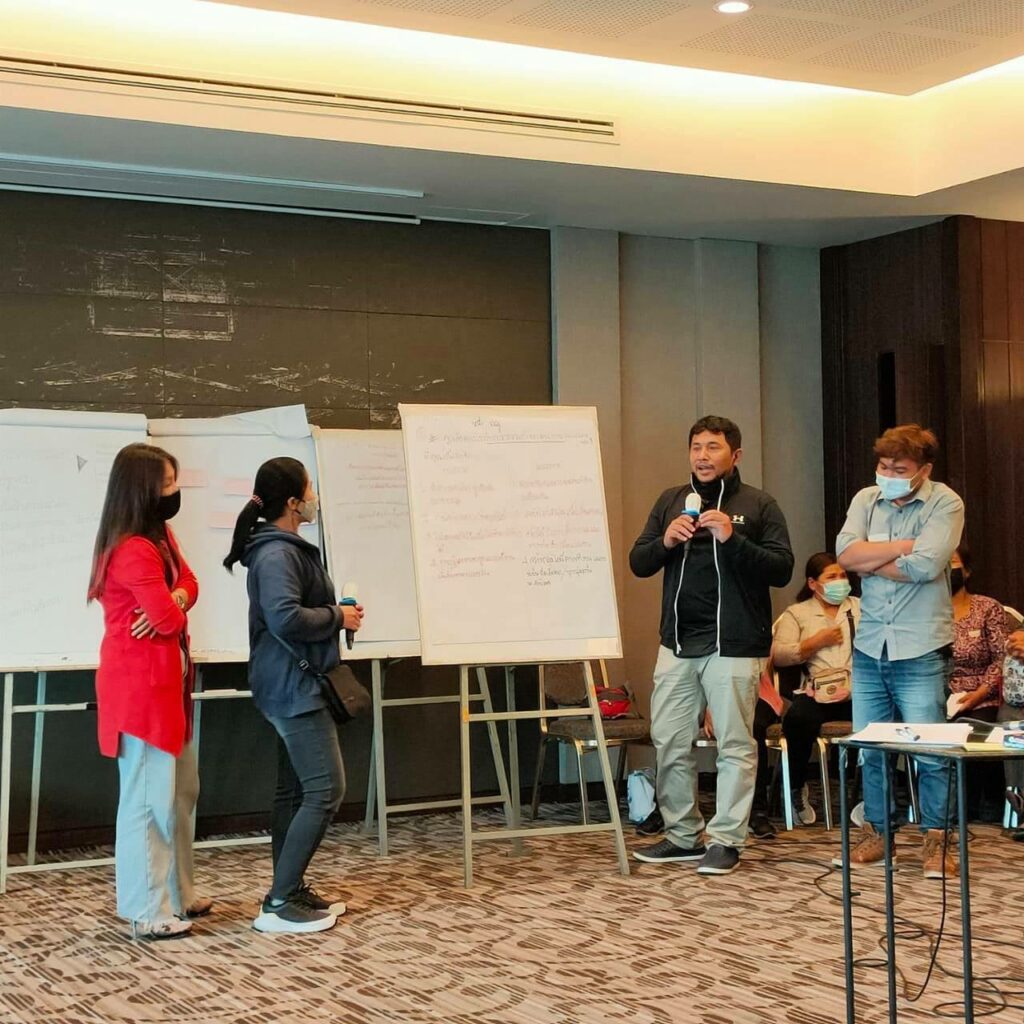

Just Economy and Labor Institute (JELI), the Labor Committee of the House of Representatives, Chulalongkorn University’s Institute of Asian Studies, and the Friedrich Ebert Foundation (FES), together with platform worker representatives, held a seminar titled “The Platform Economy: Workers Shaping the Future of Employment”, seeking to understand the problematic situation of platform workers. They discussed solutions to combat unfair employment status, long-term policymaking and the establishment of a working group to review legal protections from the government sector, and the direction of the labor movement as a whole. The national workshop took place on March 15-16 of this past year.

5 unfair issues that oppress platform workers

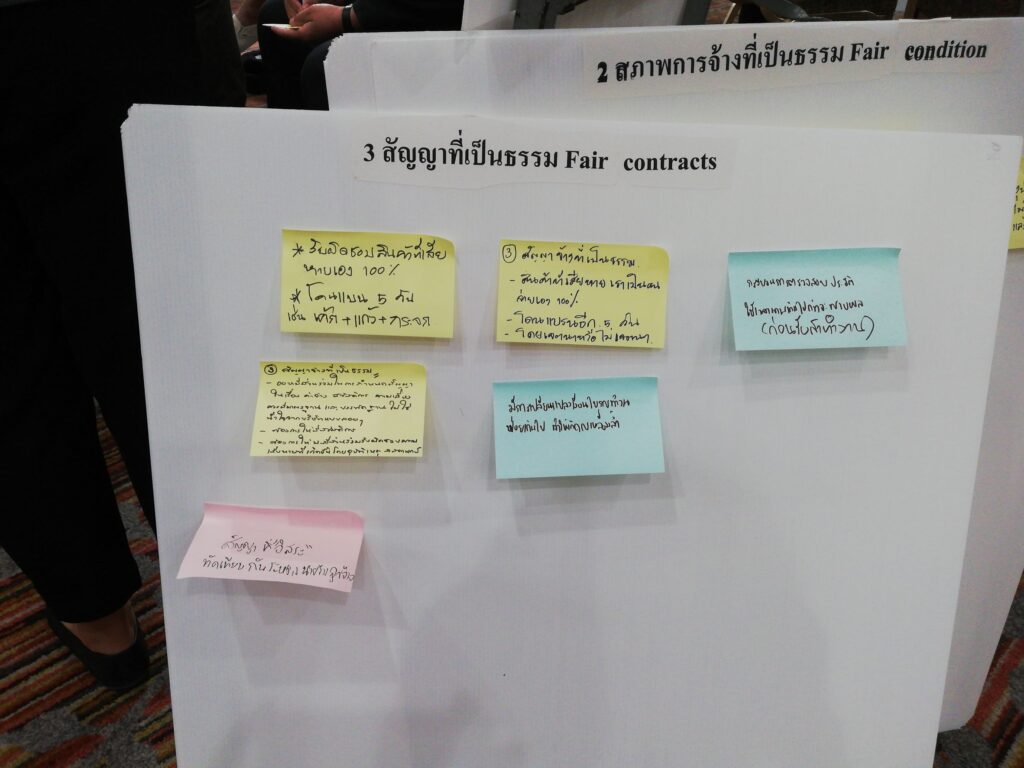

Representatives from groups of housekeepers, massage therapists, and delivery drivers (for food and rideshare services) brought up various issues during the “Voices of Platform Workers” workshop. These injustices which platform workers face can be broken down into five categories: compensation, employment conditions, contracts, management, and the company not listening to workers’ grievances. All of the represented groups have experienced unfair treatment by online platform companies.

01 – App-based Domestic Workers Group

The platform workers in housekeeping remarked that when they first started their jobs, they did receive adequate compensation. The income was satisfactory in the beginning. However, after working for a period of time, their income decreased due to deductions from increasing expenses for various things. Their income compared to the money which they had to spend for their job made it so that it was almost not worth working at all. They said:

“We have travel expenses, daily food expenses, and even the cost of cleaning supplies to take into account. We have to pay for all of this ourselves.”

In addition to this, there are also problems regarding when wages are distributed. For example, some applications distribute wages the next day. However, some may take up to 15 days after the workday.

As for employment conditions, the companies only compensate workers for the days they work. They receive no pay for days off or holidays. The companies provide no social security or welfare. If they are sick or in an accident that requires them to take a day off, they have to forgo their income for that day.

One app-based domestic worker elucidated, “For example, I had an accident where my motorcycle taxi fell down and I hurt my leg. I had to stop working for two weeks during which I received no pay to help me. There is no social welfare that the company pays. I had to go file various tax deductions myself. While my wages were already reduced, 3% was deducted per worksheet. So if the company pays 600, there’s also that 3% deduction. Then, when they transfer that money to my bank account, there’s a transfer fee of 2 baht per sheet.”

Regarding the welfare of the workers, the group of domestic workers reflected on how they had to look out for their own safety. This includes during work as well as travel, which usually requires many vehicle transfers. Oftentimes, their worksite is not on the public transit route, so they have to utilize motorcycle taxis which can also be dangerous. This is related to the work certificates issued by the companies which do not consider safety or recognize the true value of their housekeeping work.

Some worksites are so far away. Then we only work a few hours, so it’s not even worth the effort. And they’ll still deduct our expenses. And they’ll pay for the jobs without providing us with the details. It could be too far and we don’t know how the customer is. We just don’t know.”

On the issue of contracts, management, and the handling of grievances, the housekeepers explained that there is a lack of clarity. They explained that, “We only have the application with the company that owns the app so they can pay us, but there’s no contract that states how we work, or how many years. This we don’t have.” This issue of access to contracts must be addressed first and foremost. If possible, they want more fair contracts so that their opinions are heard.

They relayed their experience that, “There used to be some apps which allowed for us housekeepers to gather online and discuss our work, but when these topics of welfare and such started coming up, they’d block the groups. Even though they were the ones who created these groups.”

Read “The 3 wishes of ‘delivery maids’”

02 – Off-site or home-based Massage Therapists Group

On the question of fair compensation for the group of home-based massage therapists, they largely agreed that 200 baht per hour was fair en

ough. But what they saw as unfair was the addition of activities that go beyond what is stated in their agreements. For example, it could say a relaxing massage, but the customer will request a deep tissue massage. This happens up to 90% of the time, which is not fair to the workers. Other expenses which massage therapists have to put out are internet fees, which average around 1,300 baht per month. With traveling expenses and the cost of massage equipment added on, it is hard to determine their exact income. Their employment is not fixed because it depends on the amount of hours of work they receive per day. They receive no pay for days off, and are actually deducted 500 baht on days they request off. In addition, because of the circumstances arising from the COVID-19 pandemic, the companies have been offering certain promotions which push prices down even further.

As for employment conditions, the company provides no insurance and no overtime. Because the majority of these workers are women, they face a high risk of sexual harassment. When they face health problems, such as common injuries in the arms and fingers, they have to pay for the treatment themselves, or utilize the 30 baht healthcare system. When they are sick and have to take two weeks off work, they receive no pay.

Regarding unfair contracts, the massage therapists said that they are essentially forced to accept jobs. They are usually encouraged to take on the work as supplementary income. However, it is common that they are coerced into making it full time work. For example, if they don’t accept an assignment, they will be banned or simply not given any more work. This functions as punishment for not working full time. “I signed a contract as a part-time employee, but the employer will say that I’m an independent worker– to avoid something? Because as part-time employees, we should be receiving various welfare benefits. But when they use the term ‘independent worker’, they don’t have to give us that. There are also various regulations that force us to deduct money from our paychecks, like not following dress code. If we don’t wear socks, we lose 50 baht. For broken, forgotten, or damaged equipment– another 50 baht. All of this is unfair.”

The workers also reflect on how unfair management is, and how they do not listen to the workers’ opinions. Or the company may listen to the grievances, but will not do anything about them. Despite the fact that the company has the power to decide right or wrong, they will largely ignore any issues raised. The company will always choose to listen to the customer. “When there are two customer complaints, they [the company] will dismiss us, and we’ll receive no compensation or anything. But when it comes to complaints about the customer, action is often delayed. For example, if the customer violates the contract such as acting in a way that constitutes sexual harassment. With some companies, massage therapists can cancel the contract and leave immediately. But after the complaint reaches the company, it takes so long for them to ban this customer that by the time they do, almost all of the employees will have experienced harassment by this customer. It just takes so long for the problem to be resolved.”

With problems such as this, they see it as unfair that the company does not listen to or act on their grievances. They also do not see the point of having an assigned representative to accept opinions or the advantage of having an agent to bargain because past experience shows that the company just will not listen.

“The more we negotiate, the more we get de-activated (from the platform), and the more jobs we lose. We’ll continue to get bullied by receiving less work or getting banned completely. That’s why we don’t want representatives or a union.”

03- Delivery drivers- food and passengers

“The starting wage was 60 baht, and I was deducted 15%. Now I have 30 baht, deducted 15%. This is not fair for the rider. While riders in Bangkok have two hundred thousand users, I was taxed by the company. But the company does not issue tax withholding paperwork. Where does that tax money go? Why don’t we get it? They say we don’t pay taxes, that they don’t take a cut. So what about this deduction? Some companies it’s 10%, some 20-30%.”

A representative of the app-based delivery workers pointed out the unfairness of the compensation they all receive, providing information on how drivers typically get 60% of their wages, with 15% deducted by employers. Each app is different with their starting wages– they may start at 30, 40, or 60 baht. There is no standard for employment. Besides that, there is also an initial starting cost for the app which is 200 baht. If there is a penalty or fine, the drivers have to pay that again. Another expense are the uniforms, which used to be free, but now must be purchased. With the rest of the equipment, the total amounts to two thousand baht. Then there is the issue of distance. Before, it was no more than 5 kilometers, but now it has increased to 8 kilometers. And the system is set up in a way which makes riders compete with each other, pushing distances up to 15 kilometers. The driver is obliged to accept that order or there will be consequences with management.

“In the past, rideshare was a supplementary occupation for Thai people, but not anymore. They exploit us like slaves. I make a 10-kilometer trip for 40 baht. If I end my shift, 200 baht is deducted and I can’t work for another 24 hours. What will my wife and kids eat? We used to be freelancers. We were able to end when we wanted to. Sure, determine how many rides can be rejected per day. But they’ll deduct money and shut down the system. It’s not fair. And they’ll give out promotions to lower the price for the customers. I used to make 10 trips and get 1000 baht. Now I make 20 trips and get 700.”

A delivery driver is 100% responsible for a lost or damaged product. For example, if an accident occurs while transporting food, the driver is unable to claim the cost of the order, even for risky items such as cakes or fragile vases. If the product is affected and the customer complains, the driver must take full responsibility. Regarding compensation for the deliveries, there is no fixed minimum or maximum. To receive minimum wage, there is only stipulation that the maximum distance is 15 kilometers per job. This means that the driver may have to go back and forth for a total of 30 kilometers, for a mere 50 baht wage with the company’s 5% deduction and tax on top of that.

As for employment conditions and welfare, the group of delivery workers pointed to conflicting facts. The company generally does not provide accident insurance, but will offer it when the driver reaches 200-400 rides. But in reality, this is rarely the case, because there is a condition which says that the expenses must exceed the Compulsory Motor Insurance by ten thousand baht to be able to use it. One driver shared his experience that, “When I had an accident and phoned the call center, they told me to use the Compulsory Motor Insurance which was the preexisting insurance I already had.”

An issue that these platform workers consider to be extremely unfair is how inconsequential their complaints are. The company only chooses to listen to the customers. They never listen to the employees. For example, a customer insists on the driver running a red light because they are in a rush, but the driver refuses to because it is dangerous, so the customer files a complaint to the company. The company will then deduct points from the driver without listening to their appeal, and warns that they will be banned from the system if it happens three more times.

Further, information was provided that company regulations often change without notice to platform workers. Even though these changes concern various driver regulations, there will be no notification or consent for the group of people the company calls “partners” in the event of a rule change. When the drivers inquire, the response is usually along the lines of, “When you get a job with a company but can’t accept the conditions, you don’t have to work.” The drivers see this as the company using pretexts to legitimize itself, while shrugging off all responsibility.

“Now, various punishments and cutoffs to our livelihoods are taken advantage of, and we are unable to protect ourselves. I really don’t deserve to be taken advantage of like this, because of these unfair laws.”

Read more here on delivery drivers and painkiller dependence.

Do these labor protection laws only exist on paper?

A representative from the Department of Labor Protection and Welfare, Supisan Paluh Nittikorn, was able to answer questions from the three groups of platform workers, beginning with an explanation of their employment status. She explained the two different forms of employment, the first being between an employer and employee with a clear employee contract, and the second being between an employer and contractor. The platform workers fall into the second category.

“Contract employment is when a contract worker agrees to give their labor to an employer for a certain amount of time, primarily focusing on the outcome of the job. There is no clear division of labor. Penalties during this period fall according to the responsibilities of the worker under their contract. Looking at platform work, it is rather independent in nature: They choose their start and end times, compensation is based on kilometers traveled. The measure of success of the job is to successfully deliver products to customers.”

“I think that these characteristics fall under contract labor. The workers asked if it was illegal for the company to set working hours. Employment criteria falls under the Labor Protection Act. In terms of working hours, employers must set them, with certain rights like days off for holidays and overtime pay. Therefore, we need to find out more from the workers to know which laws are relevant.”

There is also the issue of complaints from platform workers who felt their rights which are stipulated in labor protection laws, such as those concerning wages, were being disregarded, such as with their wages. Lawyers from the Department of Labor Protection and Welfare provided information that workers can follow procedure to file a complaint with a labor inspector.

When the worker files a petition under Section 123, the labor inspector will issue an order within 60 to 90 days, with possibility for an extension if more time is needed to collect the facts. When the employee has completed this process, the employer has the right to file a lawsuit for revocation of the labor inspector’s order to the labor court within 30 days. If the employee does not agree, the order can be brought back to the labor court for revocation again. They will then decide whether the administration is in the wrong. Here, platform workers can exercise their rights.

Regarding these issues with the platform workers, especially the delivery driver group, Supisan informed that the government had already recognized the problem, but the solution is in policy, not in lawsuits. At present, the Department of Labor Protection and Welfare invited employers to discuss issues raised by workers, and summarized the information to report to the Minister of Labor and the Office of the Prime Minister. A task force has been set up in this regard, and the director will focus on policy for the protection of workers and on monitoring various labor issues.

On the legal side, Somchai Homlaor, a lawyer and human rights NGO, explained further that according to the definition of all labor laws, the term “employer” is a person who agrees to accept an employee for wages, whereas an “employee” is a person who agrees to work for an employer to receive wages. Platform workers definitely meet the definition of an employee.

“The court has interpreted these workers as “partners”. In reality, I think that this label is absurd. Take a hairdresser who works at a salon for example– the staff who provides the service. How are they a business partner? Do they have the right to determine the conditions of their employment? It is a pity that the court does not understand. I think we have to reinterpret labor relations in policy and labor protection laws.”

Attorney Somchai was of the opinion that it was necessary to fight with detailed evidence to make the court understand that these laws must protect workers, not the employers. Therefore, it must be presented that this is for the sake of keeping the peace in society. This involves the Social Security Office too. Platform workers must know their rights to social security funds. In any case, a request must be filed for the Social Security Office to order the employer to pay the compensation.

“In this case, I think that they can take it straight from the social security fund. If the employer does not put the worker in the system, then take it from the employer. If they say that the worker is not an employee, then we must sue for revocation of this order and look at the court ruling.”

Another approach that Attorney Somchai thinks should be pushed forward is amending the law to be more comprehensive and clear, which is a long process. As for labor relations law, there are still many issues such as unemployment. The court now interprets strikes as intentional harm to the employer. The worker can be terminated without compensation, when there should be a negotiation process. Somchai also added that the issue of the labor movement should be reviewed as well.

“A union strike without direct involvement of the employer is impractical. Separating state-owned enterprises makes labor unions even weaker. These matters need to be fixed, or overhauled. We need to change this conception in society and in government that labor law is a matter of security.”

Summarizing these issues in labor protection law and reflecting on the research, Dr. Kriengsak Thirakowitkajon from the Fair Labor and Economic Institute (JELI) noted that there are Thai scholars who have master’s degrees from the London School of Economics who make comparisons between the Thai legal code with that of the British and the United States. They found that the problem is not Thai law, but the interpretation of the court. If platform workers are interpreted as “freelancers,” workers should have the rights and options to work in accordance with this label.

The diversity of jobs within platform labor is a challenge. If the work is truly independent, then workers must have the right to choose freely. But when you look at the facts of these various jobs, you see that it is not independent work. The option must be there for the worker to choose the status of their work, which will involve legal battles and amendments to existing laws in the future.”

Dr. Kriangsak proposes a decision-making measure based on case studies from abroad such as America’s ABC Test. It is used to assess whether platform workers are employees of platform companies or not. If this approach is adopted and used in the court as a tool of interpretation, it may not be necessary to amend an entire set of laws.

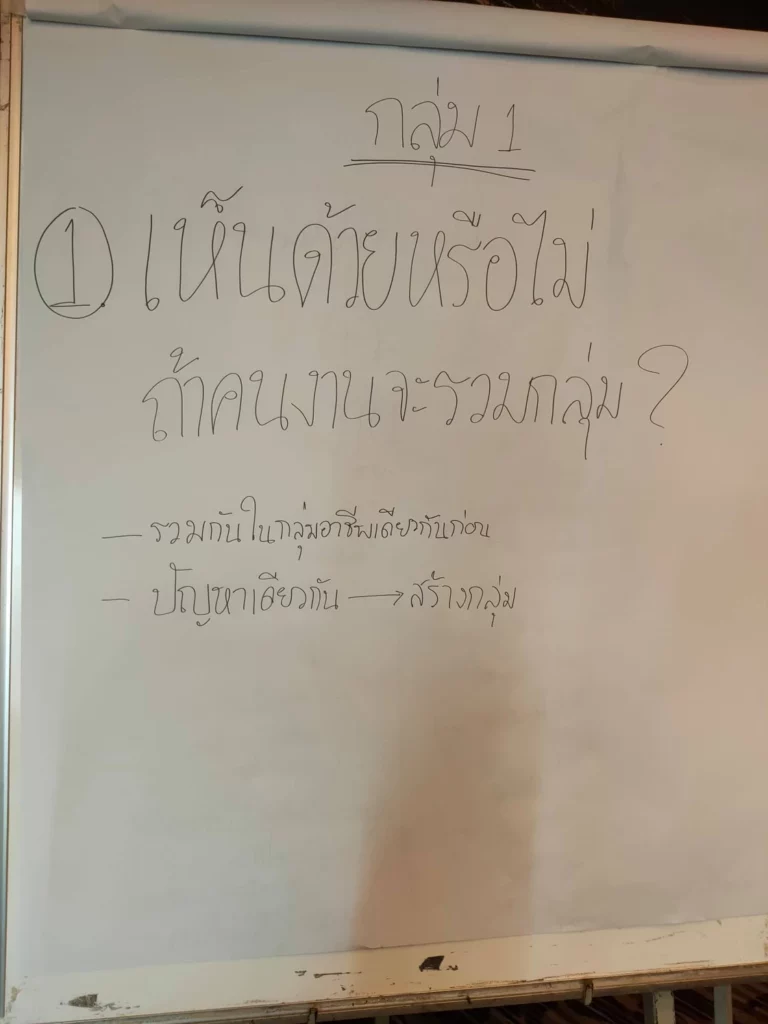

From problem to conclusion: Introducing the Task Force for Platform Workers

The right to collective bargaining among Thai workers is relatively low compared to other countries. That’s why Thailand is an attractive country for investment. When it comes to negotiating, the trade union must know who they are negotiating with, because the “employer” is not just an employer in an establishment. In some countries, we see negotiations with employers’ associations in the platform business. The union must know the competition in Thailand and in ASEAN, and where the employer or business is profiting. The surplus value taken from the wage workers is taking what form?”

Premjai Jaikla from the International Labor Organization (ILO) pointed to the strategy of “know them, know us” to effectively move the labor movement forward. This is in line with the opinion of Dr. Thon Pitidol, director of the Center for Research on Inequality and Social Policy (CRISP), who provided information from academic research which found that the bargaining power of labor unions in Thailand is considered to be relatively low. This is why platform companies are deciding to set up in Thailand. “Looking at foreign cases, there have been accommodations made for workers’ demands within the platform business. But they have to be collective demands. It also cannot be the platform workers alone, but the wider organized workforce as well, in order to create more bargaining power.”

The importance of organizing to create a powerful labor movement is reinforced by Jadet Chaowilai, director of the Women and Men Foundation. He has more than 30 years of experience in social activism and the labor movement, and believes in the power of laborers coming together.

“My opinion is that we must think of ourselves as workers as well. We must fight together. I

don’t think policy matters much. If there is a social movement, law and policy will follow on its own. But if you are not clear, if you do not organize, if you do not form groups to support the people, no matter how many times you hold seminars, it will be useless. Because organizing did not take place. Their voice is important, so I want a solution which involves gathering and talking about these issues more, creating networks to make things happen.

This is something that I think needs to be done urgently. Secondly, we need a progressive system. We need MPs who understand. They ramble on, but what’s important is policy. What is important is the workers’ movement. Therefore, the workers in the delivery, massage, and housekeeping groups must work together, and labor unions must support them.”

The workshop seminar for the participation and call for platform labor justice has come to a concrete conclusion. Sakdina Chatrakul Na Ayudhya, the scholar who has been constantly working on this issue, has collected every issue from the brainstorming process that is based on the problems of platform labor along with opinions from the joined public sector and independent entities, with an emphasis on the proposal from the head of the committee on labor. He proposed they should establish a working team that specializes in this issue. The work procedure should encourage participation and cooperation with various groups of people. The core team might be the Ministry of Labor cooperating with the House of Representatives Committee on Labor, the Ministry of Digital Economy and Society, and other sectors including academia, but most importantly, the laborer who holds the direct stake.

Suthep Ou-oun, the head of the Committee of the House of Representatives, answers to this guideline to advance to building the working group. He sees its importance and promises to proceed to the policy level.

“I am glad to kickstart the National Task Force and invite the relevant sectors to have a conversation on how to solve these problems and how to move it forward. We have to join hands together by starting here. I will talk to the Secretary to see if we have the budget. We need to help the labor organizations and worker participants gain negotiation power. We must open the floor for them like today. The people’s tax should be allocated to support this.”

This article is originally written in Thai by Anoma Sornpali and published by Decode at https://decode.plus/20210405/. The English version is translated by Rose Schweis.